When I was eight years old, I sang in a children's choir. The conductor would announce proudly, “And now, with lyrics by the famous children's poet Sergei Mikhalkov and music by Hungarian Communist Ferentz Sabo — a song about Pavlik Morozov!”

Ours were not the only voices lifted in honor of the heroic Pavlik Morozov. For half a century, the whole country lauded this brave teenage boy. I need only recall some of the rhymes of Mikhalkov's song to give you an idea of Morozov's extraordinary reputation: Pavel/marvel, revolution/execution, expose/depose, brave/grave, story/gory.

What was the deed that made him a hero? In 1932 Pavlik Morozov exposed his father as an “enemy of the People.” He informed the OGPU (as the KGB, or Soviet secret police, was then called) that his father was helping the kulaks, successful peasants who refused to relinquish their land and livestock to the State as was required by the Collectivization Plan, and was therefore branded as an enemy of Socialism. Pavlik's father was arrested, tried, and sent to a concentration camp, never to be seen again. Soon after his father's trial, Pavlik was murdered by “enemies of the State.” After his death, he was hailed as a hero of the people, and every child in the Soviet Union was required to learn his story and be prepared to follow his example.

Indeed, it is virtually impossible for someone not born and raised in the USSR to appreciate how all-pervasive a figure Morozov was. Mikhalkov, who managed to condense the entire history of Pavlik Morozov into eight couplets, was not the only one to exploit this piece of Soviet history. Another famous Soviet poet, Stepan Stchipachev, wrote a long epic poem about Morozov. The composer V. Vitlin wrote a cantata for choir and symphony orchestra in praise of Morozov. There was even an opera written about him. Many of the greatest Soviet talents used their art to glorify the heroic deed of Morozov. Sergei Eisenstein and Isaac Babel worked on a film about him, and Maxim Gorky, in his speech to the first general meeting of the Union of Soviet Writers, called on the government to erect a monument to the hero.

As a consequence, everyone in the Soviet Union, young and old alike, used to know about Pavlik Morozov. His portraits appeared in art museums, on postcards, on match-books and postage stamps. Books, films, and canvases praised his courage. In many cities, he still stands in bronze, granite, or plaster, holding high the red banner. Schools were named after him, where in special Pavlik Morozov Halls children were ceremoniously accepted into the Young Pioneers. Statuettes of the young hero were awarded to the winners of sports competitions. Ships, libraries, city streets, collective farms, and national parks were named after Pavlik Morozov. His official title is Hero-Pioneer of the Soviet Union Number 001.

In 1982, on the fiftieth anniversary of the heroic death of Pavlik Morozov, the press called the boy “an ideological martyr.” The place of his death was described as a sanctuary and the child as a saint. This was remarkable language for the atheistic Soviet press and revealed the theological nature of Communist ideology. In a thousand years of Russian history, such glory had never before been bestowed on a child.

At that time, I was still living in Moscow. I became curious about Pavlik Morozov's story and decided to investigate this child-hero.

I began by reading book after book. Remarkably, there was no agreement about even the simplest historical facts. For example, Pavlik Morozov's age at the time of his heroic death was reported as anything from eleven to fifteen. As for the village of his birth, Gerasimovka, sources placed it variously in the provinces of Tobolsk, Obsko-Irtishsk, and Omsk (in Siberia), as well as in Sverdlovsk in the Northern Urals. The photographs of the hero that were printed in various publications appeared to be of completely different people. In addition, I found as many as ten different persons identified as his murderer. Still another thing puzzled me. It was sometimes mentioned that Pavlik's younger brother, Fedya, also an informer, was murdered along with him, but it was never explained why he did not become a hero.

My surprise grew when I tried to obtain material from various state archives. There I always received the same answer: “We have no documents on Pavlik Morozov.”

I finally managed to locate Gerasimovka in Western Siberia. Boarding a train for the 36-hour ride, I headed for the boy-hero's home. But even there, in the Pavlik Morozov State Memorial Museum, there was not a single personal item, not a page from his school notebook, not one family relic to be found. I visited other Pavlik Morozov museums and instead of original documents found only sketches of the boy, books, and newspaper clippings. Relics from saints of a thousand years ago are sometimes still extant, but I could find no traces of this twentieth-century saint. I began to wonder if the boy ever existed other than as a fictional character in Soviet literature.

But one last bridge to the past remained: living witnesses. When I inquired at the museum in Gerasimovka whether I might meet with any of the witnesses, I encountered apparent resistance. “Tourists should not meet with villagers,” objected the guide. “The peasants don't understand anything and might say the wrong thing. The museum guides have mapped out your tour so that you can visit the places of interest and then leave the village.”

After being ushered on my official tour, however, I didn't leave. But everywhere I went I was accompanied by the director of the museum, so I couldn't talk to people or take photographs. I left the village for a nearby town and slipped back a few days later. I quietly started going from house to house, avoiding the attention of officials. Even so, most of the villagers who were willing to talk with me at all were reluctant to answer direct questions.

In spite of these difficulties, the evidence of the eyewitnesses of the events in Gerasimovka gave me more information than I had thought possible. The official texts turned out to be rife with lies.

I met Elena Pozdnina, Morozov's schoolteacher. She had saved a photograph of her class from the year 1930, showing herself and Morozov among a few dozen village children, some of whom were still living in Gerasimovka. This seems to be the only authentic photograph of the boy, taken, according to Pozdnina, on the one occasion in Morozov's life when a traveling photographer visited the village. When I saw that unpublished photograph it became clear that the pictures of the boy in every encyclopedia, schoolbook, postcard, and postage stamp had been so routinely retouched that they had lost any resemblance to the original.

The villagers told me that mysterious events had occurred even after the murder of Pavlik Morozov. The house in which the boy and his family lived burned to the ground. The villagers believed that it was arson, but it was never investigated. And the grave of Pavlik Morozov and his brother had secretly been moved at night from one place to another.

Early in my investigations, I established three reliable facts. First, the legendary Pavlik Morozov had actually existed. Second, he really was killed. Third, his funeral took place on September 7, 1932, although it is not known when he was actually killed.

I realized that to find out what had happened nearly fifty years earlier, I would have to make haste. The surviving witnesses of the tragedy ranged in age from sixty-five to one hundred years. In just a few more years, most of them would be dead.

Private inquiries were always very hard to make in the Soviet Union. And since this was one of the untouchable subjects, any questioning of the standard history was risky. I had to make my inquiries cautiously.

I traveled to eleven cities to track down participants and witnesses of the story. I recorded the testimonies of Pavlik's former schoolmates and neighbors, two of his schoolteachers, his younger brother, Alexei, and even his mother, Tatyana Morozova. I also talked with one of the main actors in the tragedy, Pavel's cousin Ivan Potupchik, who was a secret informer in 1932. He later became an official employee of the regional OGPU. It was he who discovered the children's bodies.

Unfortunately, the official propaganda had done its work. Morozov's biography had been greatly embellished during the fifty years since his death, and Pavlik's schoolmates remembered him mostly from reading about him. Even his eighty-year-old mother, who told me things about her son that had never been published, added: “Whatever is written in the books is correct.” A classmate of Pavlik Morozov summarized the relationship between truth and myth this way: “I will tell you how it was, but before you publish it, you must change it as necessary. You know how these things should be done.” Even uneducated people knew the rules of the game.

None of the original journalists who were sent to Gerasimovka to write Morozov's story were still alive, but I was able to locate many of their families. In some cases family members allowed me to study their personal archives, including many unpublished documents. And later, in the homes of villagers who witnessed the bloody tragedy, I was shown documents, preserved by pure luck, that helped to fill in the gaps in human memory.

But the more I spoke to witnesses and studied personal archives, the wider became the gap between the child who looked younger than his age in the only extant photograph and the brave Young Pioneer who stood up to the enemies of Socialism. After all the research, my image of Pavlik Morozov split in two. One was a country schoolboy; the other, a hero in bronze. The first one died on the day he was brutally slaughtered in the woods. The other, an immortal hero, was born that day — a model of the new Soviet man.

Maxim Gorky called Pavlik Morozov “a small miracle of our times,” and Nikita Khrushchev, in his preface to the 1962 edition of the Children's Encyclopedia, called Pavlik Morozov an “immortal of this age.” But the villagers primarily remembered the boy as a hooligan who smoked cigarettes and liked to sing obscene ditties. One of his teachers even thought he was mildly retarded, perhaps due to his mother's mental problems and his father's alcoholism. At the age of about twelve, he was still in first grade.

After extensive interviews and a thorough combing of the archives, I was able to piece together a reliable history of this child-hero.

|

|

|

|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|

|

|

|

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|

|

||

| 9 | 10 | ||

He was named Pavel and called Pashka. In real life nobody ever called him Pavlik. This tender diminutive was not given to him until after his death and first appeared in an article in the Communist newspaper for children, Pionerskaya Pravda. From then on it became his official name.

The grandfather of the real Pavlik Morozov settled in Gerasimovka in 1910. Along with other settlers, he came from Byelorussia looking for available land. His son — Pavel's father, Trofim Morozov — was a soldier in the Red Army during the Civil War. By the beginning of the 1930s, he was chairman of the Village Council.

The exact date of Pavlik's birth is unknown. The Soviet encyclopedia says he was born on November 18, 1918, but the monument that stands on the site of his burned house gives his birthday as December 2, 1918. Even his mother could not remember his actual birth date.

At first the Collectivization Plan did not affect so remote a place as Gerasimovka in the Ural administrative region. But in the early 1930s thousands of peasants from European part of Russia were exiled to Siberia, and some of those exiles settled in Gerasimovka.

The regional authorities began to follow the example of the central government and arresting those who resisted collectivization. It was a sad irony that at the same time exiles were arriving in Gerasimovka from elsewhere, residents of Gerasimovka were being exiled to even farther-flung parts of Siberia. One person's home became another person's place of exile.

At the time of this nationwide tragedy, which took millions of lives, a smaller but nonetheless dramatic event occurred in Gerasimovka. Trofim Morozov left his wife, Tatyana, for another woman. This was an extraordinary thing to do at the time. Peasants commonly beat their wives, but they did not abandon them. Pavel, about age thirteen, was the oldest of four sons. The youngest was about four. Pavel's schoolmate Dimitrii Prokopenko recalls, “When the father left the family, his responsibilities fell on Pavel's shoulders: to take care of a cow and a horse, to clean the barn, to collect and bring firewood from the forest.” For a while Trofim provided the family with some food, but then he stopped. Pavel and his mother thought they could scare his father into returning. If Trofim had not left the family, there would have been neither denunciation nor murder nor heroism. But this was not for the press.

Kabina, another of Pavel's schoolteachers, believed that Tatyana Morozova encouraged her eldest son to complain about his father to the local OGPU. “She was an illiterate, ignorant woman,” Kabina told me, “and she harassed her husband as much as she could after he left her. She taught Pavlik to inform, thinking that Trofim would get scared and return to the family.”

But things turned out differently. Trofim was arrested, and OGPU officials instructed Tatyana and her son on how to testify at the trial. All the witnesses I spoke to agreed that the boy did not seem to understand what was going on.

Trofim Morozov was sentenced to ten years in prison and disappeared forever in the camps.1 The court also ordered the confiscation of all his property. Since his second marriage was never legalized, his first family's property was seized. Tatyana and her four sons were left destitute. The villagers say that after the father's arrest, the Morozov children were constantly hungry and were grateful even for a piece of stale bread.

After being the center of attention as the prosecutor's key witness at his father's trial, Pavel became a regular informer. Survivors told me that he terrorized the whole village, spying on everybody. Having been a pawn in the family conflict, he became a pawn in the villagers' conflict with Soviet power over the demand that peasants become part of a collective farm, or kolkhoz.

There was no mention at all of the heroism of Pavlik Morozov until after his murder. But once he was dead, Pionerskaya Pravda wrote: “Pavlik did not spare anybody... If he caught his own father doing wrong, he denounced him. If it was his grandfather, he denounced him as well. A kulak was hiding weapons — the courageous Pioneer exposed him. A villager sold his goods in the black market — Pavlik revealed him for what he was. Pavlik was brought up by the Pioneers. He was growing up to be an outstanding Bolshevik.” This type of paragraph, without quotation marks, can be found in many books by different authors.

And here is what the witnesses had to say. His schoolmate Prokopenko: “Pavlik's heroism is terribly exaggerated. Pavlik was a hoodlum, that's all. To be an informer, you know, is a serious job. But he was just a miserable wretch, a louse.” Zoya Kabanova, yet another of Pavel's schoolteachers: “Pavlik denounced his father, but that was all. He wasn't trying to support collectivization and he didn't understand anything about politics anyway.” Lazar Baidakov, a relative of Pavel's who spent ten years in the Gulag in the 1930s, told me: “The boy himself did not play any serious role. As for why so much was made of him, you know perfectly well yourself.”

Six months after his father's trial, Pashka Morozov was still unknown outside his village. But then he and his little brother Fedya were brutally slaughtered in the woods not far from their home, where they had gone to collect wild cranberries. Their bodies were discovered three days later by Ivan Potupchik, Pavel's cousin and an informer for the local OGPU, who called together all the villagers. He immediately declared that Pavel was a “hero-activist-Pioneer-Bolshevik” and had been slain by the enemies of the people, the kulaks.

In the personal archives of Pavel Salomein, the first journalist who was sent to Gerasimovka to cover the story, I came across a number of remarkable documents given to him by the OGPU as supporting material for a book he was assigned to write about the hero. Among them was a copy of File No. 374 from the regional OGPU's investigation of the murder of the Morozov brothers. It contained, among other things, a “Special OGPU Memo on the Terror”2 listing the names of ten villagers from Gerasimovka who “on different occasions had been observed to demonstrate an anti-Soviet attitude.” Right after Pavel's murder, all those on the list — Pavel's grandparents among them — were accused of murder, arrested, beaten, and sent to the OGPU investigation prison. Meanwhile, a rumor was deliberately spread in the area that all who opposed collectivization would be arrested. After that, the local OGPU reported to the central Party authorities in Moscow that a collective farm had finally been established in Gerasimovka, where the peasants had resisted it for a long time.

There was virtually no investigation of the murders. The brothers were buried, by OGPU order, even before the investigator arrived. It was never established exactly when they were killed, and no medical experts were ever consulted. Available documents differ on the number of wounds and the nature of the murder weapons. The main pieces of evidence were a bloody knife and some blood-stained clothes, which belonged to Pavel's cousin, Danila Morozov. The day before the children disappeared, Danila had slaughtered a calf for Pavel's mother, who took the meat to the market in a nearby town the next day. Danila made no attempt to hide the bloody knife and clothes, and no expert was brought in to establish whether the blood was human or animal.

No significance was given to the fact that none of the accused attempted to escape or to hide the “evidence,” even though they had three days to do so. Furthermore, the boys' bodies were left in plain sight near the road, but they weren't “discovered” until the third day, which may indicate that they were moved to that place three days after they were murdered.

Two months later, in the nearby city of Tavda, an open trial was held, which the press described as the “trial of all kulaks.” The trial was widely publicized throughout the county. Four villagers, all said to be members of the “kulak anti-Soviet band,” were found guilty of Pavel's murder and sentenced to death under Article 58-8 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Republic for “terrorism against representatives of the Soviet Government.” So it was that Pavel became a representative of the Soviet State after his death.

None of those sentenced confessed to the murder. They were all members of the Morozov family: Pavel's grandfather, Sergei Morozov, 81 years old; his grandmother, Ksenia, 80; his godfather and uncle, Arsenii Kulukanov, 70; and Danila Morozov, 19, who had gone to school with Pavel. All four were executed immediately after the trial.

Also in Salomein's archives, I came across a mysterious unnumbered document of the Ural OGPU Secret Department. It was the record of the interrogation of Ivan Potupchik (who found Pavel's body) by an OGPU investigator, Spiridon Kartashev. Potupchik, according to the document, testified that the murder of Morozov had a “political character because Morozov Pavel was a Pioneer and an activist and spoke out in public meetings on behalf of the Soviet State and to expose the kulaks of Gerasimovka.” Further on, the “record” gives a detailed account of the heroic deeds of the Pioneer.

The most remarkable fact about this document is that it is dated September 4, 1932, two days before Ivan Potupchik is alleged to have found the bodies of the Morozov brothers. So it appears that while all the villagers, including Pavel's grandparents, were searching for children, thinking that they were lost in the woods, the OGPU agent and his informer had already described the murder and identified the ten individuals who would later be charged as kulaks and as Pavel Morozov's murderers.

This document made me suspect that Kartashev and Potupchik themselves killed the children. I spoke to both them, and naturally they denied any connection with murder. Today they are both dead, but we have the following information about them.

After the murders, Ivan Potupchik, who had formerly been an informer for the local OGPU, was officially employed in the mass executions of kulaks. Later, he was found guilty of the rape of a teenage girl and spent a short time in prison. After he was released, he was again employed by the OGPU, but received an assignment far from Gerasimovka.

Kartashev, an OGPU investigator, willingly spoke of his part in persecuting kulaks: “By my personal count, I shot thirty-seven people and sent many more to the camps. I know how to kill quietly. Here's the secret: I tell them to open their mouth, and I shoot them close up. It sprays me with warm blood, like eau de cologne, and there's no sound. I know how to do this job — to kill.”

But Potupchik and Kartashev, and even those who organized the trial in Tavda and shot Morozov's relatives, turned out to be small players. The campaign of terror was organized by much more highly placed individuals. A number of secret reports stamped “Terror, Series K” (“K” being short for kulaks) contained information about the “political murder” of Pavel Morozov and about the trial. These were prepared by the Tavda regional OGPU and then sent to Sverdlovsk, the capital of the Ural administrative region, and from there directly to the head of the special Department of Stalin's personal secretariat, Alexander Poskrebyshev.

Stalin personally ordered that a monument to Morozov be erected at the entrance to Red Square3 and presented Tatyana Morozova with a house in the Crimea, by the Black Sea. But there is no doubt that Stalin knew the whole truth.

Soon after the trial, Potupchik and Kartashev were sent away to work in the OGPU liquidation unit. Many of Morozov's remaining relatives were sent to camps. His younger brother, Alexei, who was ten years old when he testified at his grandparents' trial at Tavda, spent ten years in prison for “espionage” during the period of his dead brother's greatest glory. All the top Party officials of the Ural administrative region at the time of the trial were later purged.

Shortly after Stalin's death in 1953, an order came to officials in Gerasimovka to move the Morozov brothers' grave from the cemetery to a spot in front of the windows of the kolkhoz administration building. The operation took place in the middle of the night, with only the headlights of a car illuminating the scene. KGB officials shoveled the contents of the old double grave into a wooden box, mixing the bones of the two brothers together. They dug a deep hole, laid the box in it, and poured six feet of concrete on top of it. Erection of a monument completed the job. Any further exhumation became impossible.

Meanwhile, Pavlik Morozov had become a legend and the model of the “New Soviet Man.” The real village boy had been superseded by the official hero. “He deserved the honorable name of Communist that he carried,” Pionerskaya Pravda wrote of Morozov, even though there were no Communist Party members in the village at that time, not to mention that Pavel was too young to be one. He was also called “a deserving ward of the Lenin Komsomol” (Young Communist League), although a chapter of the Komsomol was not formed in Gerasimovka until after Pavel's death. In fact, there was no Young Pioneer chapter there either. Matrena Korolkova, Pavel's schoolmate, said: “About him being a Pioneer, the truth is they just wanted that to be the case.” And Elena Pozdnina, told me: “No, Pavel Morozov was not a Pioneer. But you must understand: to make a good hero he had to be a Pioneer.”

In Salomein's personal notes, I found this unpublished comment: “To be historically correct, Pavlik Morozov not only never wore a Pioneer tie, but never even saw one.”

Another piece of the Morozov myth was created in the early 1950s, during the campaign against “cosmopolitanism,” or Western influence and the “bourgeois liberal values” associated with it. The press started calling Morozov “a Russian boy.” Soviet Hero Number One had to be Russian. In actual fact, Morozov and all the rest of the villagers were Byelorussian.

The practice of people's informing on each other had begun in Lenin's time. Some of Lenin's early comrades recalled that he asked them to write anonymous denunciations of his political adversaries. As General Secretary of the Communist Party, Stalin routinely eavesdropped on his colleagues with a secret listening device.

It was Lenin who appointed Stalin head of the Worker-Peasant Inspection Commission, which collected compromising information about State employees. Even earlier, Stalin had begun to use the OGPU apparatus to collect compromising information, both genuine and concocted, about people who interfered with his plans. The informer system became Stalin's practical instrument for destroying his adversaries and consolidating his own position. And for his subordinates, informing was a way to prove their loyalty, to gain their leader's favor, and to further their careers.

The new Soviet citizen had a duty to inform on his fellow citizens. In this way he demonstrated his loyalty to the great goal of Socialism, in which many informers sincerely believed. And there also were those who apparently enjoyed being informers and participated enthusiastically in the denunciation campaign.

Under Stalin's direction, a State agency for the collection of denunciations was formed, a nationwide ear called the Complaint Bureau. The information gathered by the Complaint Bureau was used by the Prosecutor's office and the OGPU.

The campaign to encourage mass denunciations was carried out with great enthusiasm. Denunciations became a regular feature of the Soviet press. A newspaper's condemnation was almost as powerful as a court's sentence. The Deputy People's Commissar of Education, Nadezhda Krupskaya (Lenin's widow), instructed children to “be observant at all times in order to help the Party eradicate its enemies.” Hundreds of new Morozovs were praised in the press and were rewarded for their good work by a trip to Artek, a prestigious Young Pioneer summer camp on the Black Sea.

Feeling helpless in the face of this national tide of surveillance, people sometimes took the law into their own hands. During the years of Stalin's terror, there were at least fifty-six reported murders of young informers. Misguided by their teachers, these children, like their model, Morozov, were the victims of a political struggle they were too young to understand.

For more than fifty years, Soviet children were taught to keep a sharp eye out for enemies of the people, even among their neighbors and family members. A young Komsomol leader, A. Ksoarev, wrote in Pravda, “We do not share a common morality with the rest of mankind... For us, morality is that which builds Socialism.”

Moved by this kind of “morality,” Stalin and his government easily converted millions of living people into corpses. But in the case Pavlik Morozov, a corpse was converted into a living symbol. Through the power of this legend, Stalin raised an army of Morozov imitators, and the myth became an everyday reality of Soviet life.

Pictures:

1. 1970s photograph from a propaganda booklet: daily ritual of children putting a red Young Pioneer tie on a plaster bust of Pavlik Morozov.*

2. School class picture 1930: Pavel Morozov is in the back row, third from the right. Danila Morosov is to his left, holding a banner.*

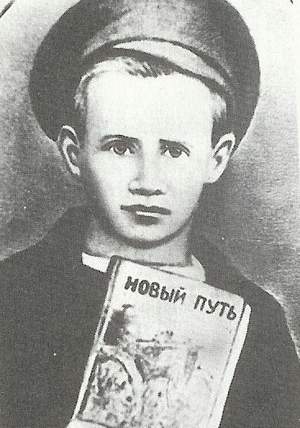

3. The first “photograph” of Pavlik Morozov that appeared in Pionerskaya Pravda ten days after his death; it seems to be based on the class photo taken two years earlier, except in the original picture he wore a peasant shirt with a high collar, but the newspaper showed him with a bare neck. That would later change to a football jersey and then to a soldier's coat.*

4. 1932 “improved” photo published in the book Kolkhosnuye Deti (Collective Farm Children): a book titled The New Way appears in his hand.*

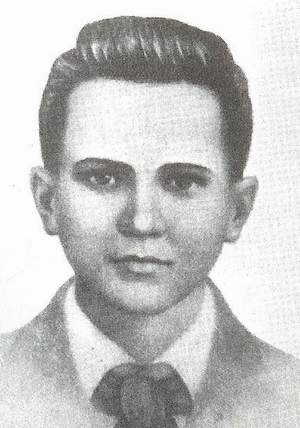

5. Morozov as he was shown by the Soviet media in the 1950s: in a snow-white shirt and Young Pioneer ties, a uniform introduced by Stalin only after World War II.*

6. Morozov as shown in a 1970s edition of the Greater Soviet Encyclopedia.*

7. Artist's impression of Pavlik Morozov in a 1972 issue of the periodical Ogonyok, in a spread celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Young Pioneers League.

8. A famous statue of Pavlik Morozov holding a flag, in a park named for him in Moscow, about 2 kilometers west of the Kremlin (now removed).*

9. Pavlik Morozov railway station at South Ural Railway, Russia.

10. 2005 picture of Pavlik Morozov Peak, Northern Tien Shan, Kyrgyzstan.

* Photos 1,2,3,4,5,6,8 from archives of Y. Druzhnikov.

Footnotes:

1. There is some indication that he was executed in a camp after his son's murder.

2. Terror against peasants was an official policy of the Collectivization Plan.

3. Later Stalin changed his mind and ordered the monument to be placed on a small Moscow street named after Morozov.

© 1993 Sonia Melnikova

About the writer:

Yuri Druzhnikov was born in Moscow in 1933. A historian, journalist, and writer, he is the author of many novels, research books, short story collections, and children's stories. He was a member of the Union of Soviet Writers until 1977, when he was blacklisted for publicly expressing his doubts about the veracity of Soviet propaganda concerning the boy-hero Pavlik Morozov. In the period 1982-1984, Druzhnikov wrote Informer 001: Voznesenie Pavlika Morozova (The Myth of Pavlik Morozov). It was published in Russian in London in 1988. It has since been translated into several languages and published in Poland, Hungary, and Latvia, and, finally, in Russia. In 1987 Dr. Druzhnikov emigrated from the Soviet Union. He currently teaches Russian literature at the University of California, Davis.

Certified Russian translation by a Certified Russian Translator: Sonia Melnikova-Raich is a Russian-English translator certified by American Translators Association (ATA). She is a certified Russian translator, certified Russian interpreter, certified court interpreter, Russian court interpreter certified by the State of California and Judicial Council of California, and a federal court interpreter. She has twenty years experience with expertise in legal translation, business translation, real estate translation, health care translation, medical translation, education translation, environment translation, communication translation, social services translation, social science translation, marketing and advertising translation and cultural adjustment, religion translation, art, film and video translation, architecture translation, and literary translation from Russian into English and from English into Russian. She works as a court interpreter for Superior Court of California, US Federal Court, USCIS (INS), Workers Compensation Board, and interprets for depositions, arbitration, trials, immigration and political asylum interviews, business meetings, and conferences. She provides certified translation of diplomas, academic transcripts, birth certificates, death certificates, marriage certificates, divorce certificates, adoption papers, immigration documents, business contracts, immunization records, and other legal documents in compliance with requirements of the USCIS (INS), US courts, credentials evaluation services, medical boards, boards of registered nursing, American colleges and universities. She can also provide a certificate of translation (affidavit of translation or affidavit of translation accuracy), and notarized translation, if needed. She translates from English into Russian and from Russian into English. She interprets English to Russian and Russian to English, performing consecutive interpreting, simultaneous interpreting, sight interpreting, and voice over. Other services include linguistic analysis of company and product names, localization and cultural adjustment, Russian-American cross-cultural communication, cultural sensitivity training, and cross-cultural conflict resolution.